Zev is a boy. He doesn’t cleave to all the gender stereotypes (he loves to dance, is emotionally articulate), but he does like war. He likes to play war, he likes to learn about war, he likes to talk about war.

While we’re mostly your basic post-hippie, peace-loving earth-parents, we decided at some point not to enforce a “no gun” policy in play. Let his natural instincts guide his play, don’t try to suppress the modes that resonate with him naturally, we thought.

Instead, I try to use his interest in war as an educational tool: we talk about martial strategies as life lessons (the importance of the high ground, protecting your flanks, the challenges of a two-front war, how infantry and cavalry work together) and I’ve used each iteration of “tell me more about war” as an opportunity for a history lesson: how can you talk about the American Civil War without talking about slavery, King Cotton and the industrial revolution? What was different about the Roman approach to war and government that allowed it to grow and expand past the Etruscans, Carthaginians, Greeks and Gauls? Why did so many more people die in World War I compared to previous wars?

While I’m quite proud of his growing knowledge and the earnestness with which he engages on these erudite topics, I still cringe when, six-year-old boy that he is, he grabs a bended straw, sites it towards an imaginary enemy and declares “pow, pow, pow!”

Oh, the indignity, what must these Dutch think of this American parenting?

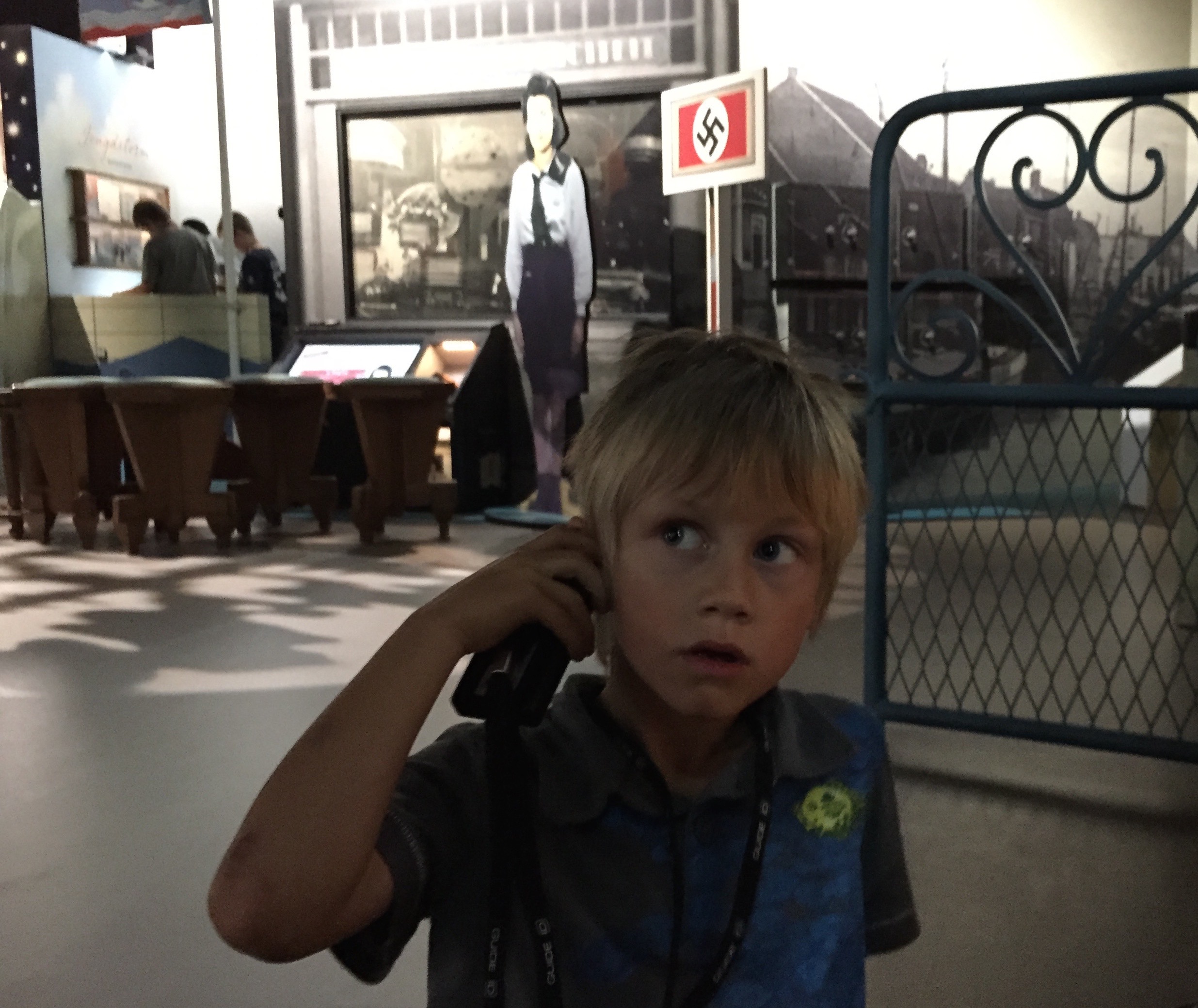

So, I’ll admit that when I suggested to Zev that we go to the Dutch Resistance Museum in Amsterdam today, I had a mixture of motives: I knew he would be excited (we’d even played “Dutch Resistance” on some of our bike rides); I also knew it would be a good history lesson for him; and, while I was nervous about exposing a six-year-old to the horrors of the Nazi occupation and the Holocaust, I did hope that a vivid illustration of how awful war actually is might temper his enthusiasm for the game.

So this bright, sunny day, we packed a lunch, hopped on our bike and pedaled the 10 minutes across the canals to the Verzets Museum, as it’s called in Dutch. We talked about war on the way over, but shortly before we arrived, I explained that because the people there may have had relatives they lost in the war, it wouldn’t be respectful to play war at the museum.

“OK,” Zev agreed, after a moment of thought. “We should stop now then, so I don’t forget.”

The museum has a powerful, unblinking but gently presented “Junior Museum” designed for children: it tells the story of four children impacted by the Nazi occupation of the Netherlands: a Dutch boy whose father is a chaplain and an active member of the resistance, another boy who regards the war as an object of fascination and then annoying disruption, but not a moral issue, a Jewish girl who has escaped from Austria, only to find the Germans descending on her new haven in Amsterdam, and the daughter of a collaborator and member of the Jeugdstorm (Storm Youth, the local equivalent of the Hitler Youth).

The museum has a powerful, unblinking but gently presented “Junior Museum” designed for children: it tells the story of four children impacted by the Nazi occupation of the Netherlands: a Dutch boy whose father is a chaplain and an active member of the resistance, another boy who regards the war as an object of fascination and then annoying disruption, but not a moral issue, a Jewish girl who has escaped from Austria, only to find the Germans descending on her new haven in Amsterdam, and the daughter of a collaborator and member of the Jeugdstorm (Storm Youth, the local equivalent of the Hitler Youth).

Each story is true (and we see, as we exit, the grown-ups they have become) told through a first-person narrative with video collages built from their scrapbooks, models of their home you can walk-through, and other interactive displays. We hear the voices of the children through our audio guides as we go.

Zev was well-sobered, and even quietly, bravely apprehensive as we entered, but scrupulously, emotionally fascinated throughout. He listened carefully to each story, stopped and asked questions when something was unclear, and reported back what he learned as we went. He looked at me with pain when we learned that one of the resistance fighters that was harbored in the children’s house had been killed by the Nazi’s, but was not terrified in an unhealthy way. The only thing that left him shaken was when one exhibit suddenly played the sound of soldiers banging at the door, demanding to be let in.

When we were in the “house” of the Eva, the Austrian Jew who was hidden in an attic (and lived across the street from Anne Frank), I was most apprehensive that I was pushing the limits of a six-year-old’s emotional capacity, but he quietly took it all in, with measured concern. Instead, it was me who had to turn away, choking back tears, when Zev opened a door labeled “Betrayal” (which he couldn’t read) and declared “look, another hiding place!”

The room was made to look like a boxcar.

I wouldn’t recommend it for all children, but it was an incredible experience for Zev, and something I’m glad I was able to guide him through and share with him.

And he hasn’t asked to play war again today.